Which of these...

...is the future of devices?

Early yesterday Motorola announced their ambitious Ara project - a modular phone with interchangable parts and features. In theory it sounds great - battery running low? Swap in a new one. Need a bigger camera for that trip you're going on? Pop one in - no need for that big DSLR.

Last week however, Apple announced something that was almost the complete opposite of that - their new line of Mac Pros. Beastly machines though they may be, they've taken a nose dive away from modularity. Custom made parts means that you can't just go down to your local Fry's and pick up a new piece if something goes wrong. Non-standard form factors and connectors mean that if you're looking to upgrade down the line, you're probably going to be out of luck. This was especially shocking, as traditionally desktops have always held their ground in the move away from modularity that's been seen in portables.

Plenty of people are upset by this. Some people are arguing that it's Apple's way of getting people to upgrade their entire computer more frequently - a devious tactic to milk their customers for more money.

I however see it as inevitability.

The issues with ara

Ara's fully modular approach has some issues. While being able to swap out parts on something like a car is great, on a phone space is a hot commodity. Any extra cubic millimeter wasted by modular interconnects is less space that could be taken up by more battery instead. Over time plenty of parts on the phone will get smaller and more power efficient, but batteries don't follow those trends. They follow a very slow, but steady trend of linear density growth - we aren't going to see a penny sized battery that can run a phone for days anytime in the near future. On top of that, there's a limit to how power efficient parts can be. Processor can have better schedualing, circuts can have smaller build fabrications that require less energy for a signal, and radios can rely on lower power frequencies (i.e. wifi) when available. But the largest power suck, the screen, is the evil step child of efficiency. Even if a screen is 100% efficient in converting electrical current to photons, it's still inherantly wasteful. A screen has to put out enough photons that a pupil two millimeters wide can capture enough light from it half a meter away. That fundamental principle isn't going to change anytime soon, and since that's the largest piece of energy consumption in phones these days, power requirements aren't going to drop significantly in the foreseeable future.

If you look at a modern smartphone's circutboard, you'll quickly see why modularizing parts can very easily take over that battery real estate. On an iphone 5s, the circutboard keeps the processor, 1GB of ram, and 128GB of storage in an area that's about the size of two quarters stacked on top of each other. If you look at some of the prototypes for the Ara, you'll notice that even their smallest size modular slots are larger than that on their own. Separating those out for convenience is going to be quite the opposite of convenient.

Size concerns aside, there's also the issue of what parts you can actually make modular. Many parts will still have to be baked into the chassis - antennae have to be spread out in order to get the best reception possible. Most phones these days also have microphones scattered around the body for noise reduction purposes, so those are going to have to be baked in as well.

A brief history of modularity

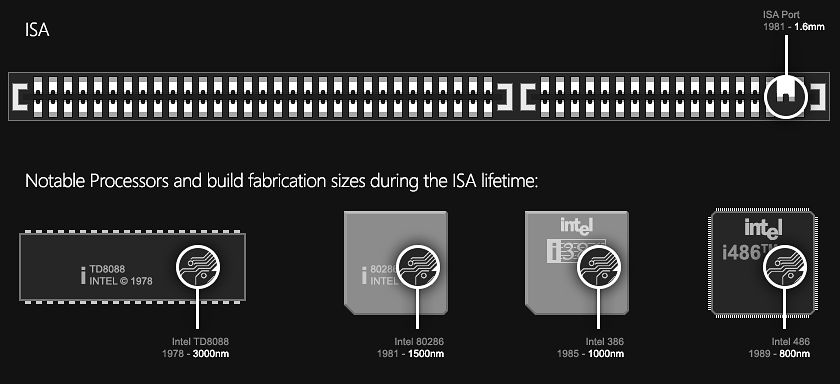

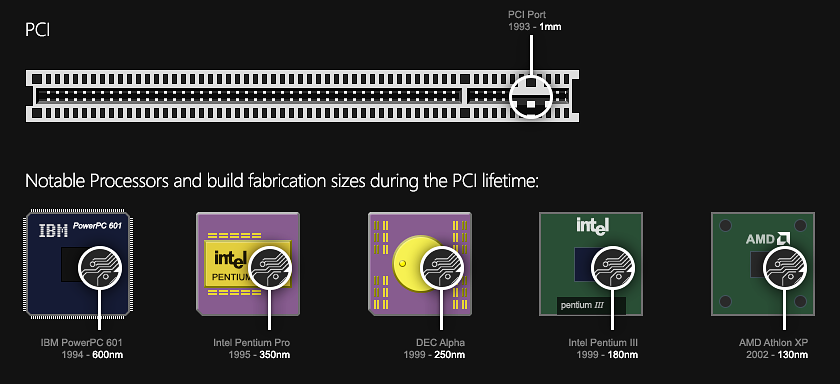

Way back in 1981 IBM introduced ISA (Industry Standard Architecture) to the world of computing. As its name suggests, it was meant to be a standard interconnect between motherboards and peripheral cards. It was fairly widely adopted, but lacked speed and adaptability. EISA was the next upgrade, but it was fairly short lived and replaced by PCI in 1993. The 32bit PCI expansion slot became the mainstay for peripherals for the better part of a decade. It ran at over ten times the speed of the original 16bit ISA spec - an impressive change, but one that would prove to not be enough for graphics cards even at the time.

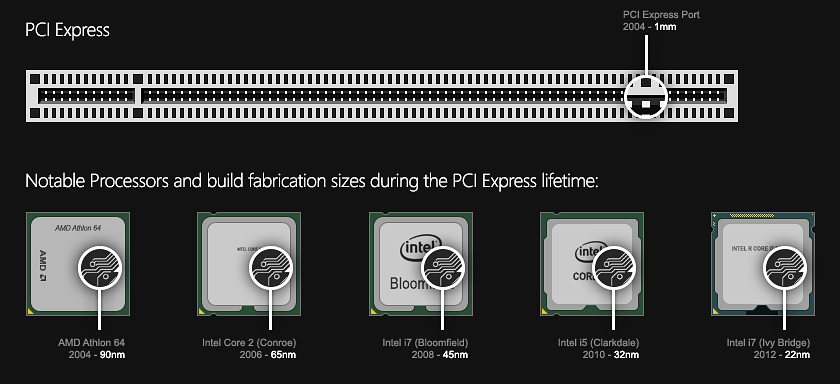

Eventually, AGP (Accelerated Graphics Port) was born to support GPUs' thirsty bandwidth consumption. AGP would live on until the modern day PCI Express was born in 2004 - the first popular standard interconnect for expansion cards to use serial communication as opposed to parallel. With version 4 of the PCI-E spec, speeds are nearly 3000 times faster than the old ISA spec.

Despite all these changes in speed, one thing has largely stayed nearly the same. The physical size of the interconnect is still limited not by our current technology, but by our ability as humans to line up copper connectors. Right now the lane size for PCI Express is the exact same as it was back in 1993 when PCI was released - 1mm. Contrast that with the lane size in a modern day processor - currently 22nm. Eventually, we're going to hit a limit with the amount of data that any individual lane can transfer (currently at a jaw dropping 1969MB/s with PCI-E v.4), simply because we can only bend the laws of physics so far. At that point, our only option to increase speed is going to be to add more lanes.

At that point, modularity will begin to fail.

Other downsides to modularity

Even if we don't hit that theoretical limit of what we can push through a lane any time soon, the other downside to modular systems is latency. Transferring things between memory caches takes time. This is one of the reasons why we have so many levels of cache in CPUs - the closer they are to the CPU/GPU, the faster you'll be able to process that data. Transferring bits of information through a PCI-E port is going to take more time than if the GPU is on board (or better yet, built into the CPU directly). This is one of the reasons behind the big push of APUs right now. By lowering the latency between the two processing units, you'll get better performance overall.

Of course though, this all comes at a cost of modularity. With an APU, you don't get to chose what GPU you have. You can't mix and match CPUs with GPUs. Your configuration options are limited to what the manufacturer decides to make.

The movement away from modularity

We're already seeing workarounds

- graphics cards are using two, or even three PCI-E slots to get that precious bandwidth they need.

This is not the case, my memory betrayed me. Thanks HN for all the corrections.

With 4k displays on the horizon, and textures in games being updated accordingly, we're going to need more bandwidth and lower latency for graphics cards. At some point, we're either going to have to switch to two dimensional connectors like processors are using for GPUs (which will still only delay our issues and doesn't address latency), or we're going to have to move away from the 1mm build fabrication for our interconnects. If the later happens, we simply can't rely on consumers to properly line up lanes in components. At that point, assembly will have to be done by machines - not geeks in their garage ordering parts off newegg.

Intel has already started doing this with their atom line of processors. It comes fused to the motherboard in order to cram as much bandwidth as they can in that small of a package. On top of that, roadmap leaks have shown intel's plans to end socketed CPUs.

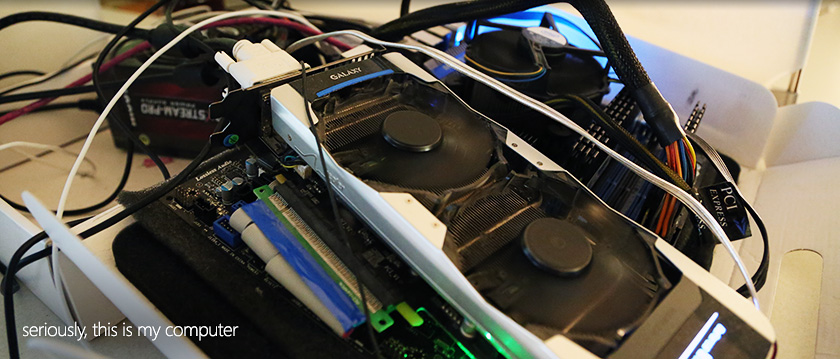

Inevitability has caught up with us. We've pushed hard to keep modularity around as long as possible. I'll certainly miss it, as I'm currently typing this article on a computer that's quite literally a pile of parts on my desk.

But in the end, it's the right step. I'd rather make improvements to speed, power consumption, size, and cost than keep the bottleneck of modularity around. Apple has made one of the first large steps away from modular computing, and while it's certainly not their first time doing so, they're going to have an uphill battle initially. At some point though, modular computers and devices simply wont be able to keep up with specs of closed systems. Precision factory manufactured machines will outperform what home builds are capable of.

This post, its content, and related files are released under a

Attribution 3.0 Unported license

. Feel free to share, remix, reuse, and learn from anything you see here. I'd appreciate credit, but if you don't I wont hunt you down.

This post, its content, and related files are released under a

Attribution 3.0 Unported license

. Feel free to share, remix, reuse, and learn from anything you see here. I'd appreciate credit, but if you don't I wont hunt you down.